Achieve.org recently posted a helpful Student Assessment Inventory for School Districts. Often assessments have accumulated unbeknownst to all stakeholders, and we should look for assessments that can be eliminated or reduced, or perhaps also where we can improve the efficiency and effectiveness of current assessments. Having gone through this process of creating inventories of assessments a number of times, I have seen certain assessments eliminated in the process. However, I have never heard anyone recommend the elimination of classroom curricular assessments; unit tests, quizzes, and other assessments tied directly to the lessons being taught. These should not be overlooked in these inventories and in fact, their importance can and should be amplified so that other assessments can be reduced.

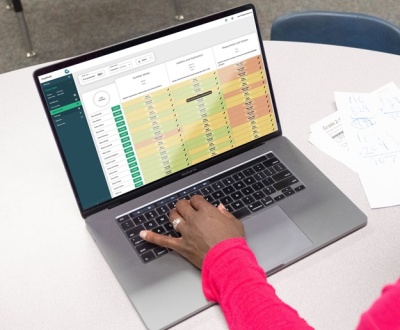

Unfortunately, Achieve’s Inventory Guide under-emphasizes the critical importance of attending to the systems used for collecting and reporting assessment results. Where is the data being stored, or are they being stored? Is there consistency in reporting, or are teachers on their own in interpreting and recording results? Are the data accessible in a form that is efficient and useful for all stakeholders? Are the data from assessments integrated, or are they isolated? What level of detail is there to the data? These kinds of questions are critical.

Take for instance the difference between classroom assessments and state tests. Teachers are awash in evidence of student learning on a daily basis. That evidence, seen in student work, heard in conversations and revealed in unit assessments and quizzes provide the most relevant and meaningful information possible for guiding instructional decision making and informing collaborative work. However, due to inadequate systems for gathering that evidence, it is largely or entirely invisible to colleagues, principals, curriculum leaders, and on up, and is often inconsistent from classroom to classroom. State tests, on the other hand, provide very visible and consistent data. In some cases, it is the only data visible to principals and other leaders. And while those state test results hold minimal amounts of truly meaningful information for improving instruction, it’s what leaders use to lead because sometimes, it’s all they have.

Middle-Layer Assessments

The lack of visible, reliable, consistent data from the classroom is in many respects what has given rise to a middle layer of assessments; benchmark and interim assessments. These middle-layer assessments, which sit between the classroom assessments and state assessments and are typically scanned multiple-choice, or computer-based assessments, and serve the purpose of providing common data visible beyond the classroom. Middle-layer assessments are not new. I remember vividly my rookie year, teaching 1st grade in a high-needs school in Denver in the late ‘90s. Every six weeks were required to administer bubble tests to my emerging readers and budding mathematicians. The bubble tests produced all sorts of charts and circle and bar graphs for principals and other district leaders to attempt to make sense of. I’ll never forget when one of my serious strugglers created a pattern when filling in her bubbles. I knew that was progress (her needs were profound). I wonder what the district leaders thought of her results. These district mandated assessments had a tangible negative impact on my class; I still remember the day Bobby refused to come out from under the table. And the reports of the results given back to me were utterly meaningless. But I understand the intentions were good; leaders need information in order to lead, and the results from my classroom assessments were neither accessible nor consistent.

Assessment techniques have improved some since those days, but we’re still stuck with too many assessments. When you fill out the achieve.org or other assessment inventory, my guess is that you will find that the bulk of the excess seems to come from middle-layer assessments. The perceived necessity for middle-layer assessments has come because the most meaningful assessment results, the classroom assessments which are closest to the lessons we teach, remain largely inconsistent and invisible to anyone but the classroom teacher, and are therefore unavailable to leaders, and only minimally useful for collaborative conversations.

Eliminate the Middle Layer

With the proper tools, however, curricular, classroom assessments can and should fulfill the same purposes as middle-layer assessments. When the results of common classroom unit tests, quizzes, and other assessments are made visible and that evidence is used to measure student progress relative to standards and relative to peers, middle-layer assessments can be partially, if not completely, eliminated. Elevating classroom assessments reduce costs, lessens the impact on instructional time, nourishes collaborative efforts, streamlines conversations, and empowers teachers, schools, districts to control their own assessments.

Some people at this point in my proposal raise concerns about the validity and reliability of classroom assessment results. Validity is the ability of an assessment to measure what it says it measures. What could be more valid for measuring leaning than an assessment that is directly tied to the material being taught? Middle-layer assessments have far too often failed to impact classroom instruction because teachers see that these assessments are disconnected from the lessons they teach, and are, therefore, not valid for informing day-to-day lesson planning.

Reliability on the other hand, although important, is virtually unimportant when assessments are not considered valid. A computer-scored multiple-choice test is incredibly reliable, but when the results are considered irrelevant, then what is the use? As the National Academy Press pointed out in, Knowing What Students Know: The Science and Design of Educational Assessment (2001; p. 100) “There is a substantial trade-off between reliability and the richness of the record.” A rich record is a meaningful record. If there must be a trade-off between reliability and meaningfulness, we must favor more meaningful assessments.

Middle-layer assessments have repeatedly failed to have a significant impact on instructional decisions in spite of their published reliability coefficients because they are largely considered invalid and not meaningful.

Forefront empowers districts to use classroom curricular assessments systematically and reduce or completely eliminate middle-layer assessments. Once the results of classroom assessments are made visible, they can be used for many purposes, including:

- As formative assessments

- To inform collaborative conversations

- To guide goal setting and monitor success

- As summative assessments to inform reporting

- Compiled, processed results can serve as benchmarks

- Tier 1 and tier 2 progress monitoring

Another place where Achieve’s Student Assessment Inventory could be improved is that it would benefit districts to think less about the types of assessments and think more about the purposes of assessments. Certainly, assessments are and should be designed for specific purposes. However, a single assessment can and often should be used for multiple purposes. For example, a beginning of year assessment for 3rd-grade math should provide formative information for the 3rd-grade teachers. But these results, if they are visible to the 2nd grade teachers, can also serve as summative data to help them understand the success of the students they had in the prior year, they can also be used to inform professional learning, improve lesson design, and if used over multiple years, are also helpful for goal setting.

As schools and districts put the Achieve.org Student Assessment Inventory to use, it will benefit them to carefully consider the systems that record and report on the results of the assessments they have in place, and how they can be utilized to improve instruction. Teachers and leaders must consider not only how we will provide forward-thinking educational experiences for our students, but also how we will harness the power of technology to learn about and improve our own practice and becoming increasingly effective and efficient in our assessment practices.

About us and this blog

Our team and tools help schools implement standards-based grading, streamline assessment systems, and use meaningful data to drive decision-making.